Diagnosing Knee Pain

If you’re feeling pain in your knee, chances are you’re not alone. “The knee is probably the most common physical injury we see these days,” says Robert Gotlin, DO, director of orthopedic and sports rehabilitation at Beth Israel Medical Center in New York City. “It’s due to the fact that we’re much more active now at both older and younger ages.”

When you go to the doctor with a potential knee injury, there are several methods to diagnose your knee pain.

Medical history: Your doctor will begin by taking a history. This is the who, what, where, why, when, and how long of your knee pain. Questions about whether the injury is acute or chronic, if there is swelling, and severe vs. minor pain will help your doctor narrow the potential causes.

Physical exam: This is usually the next step that physicians take to diagnose knee pain. Examining the knee and gently feeling it can help doctors narrow down the source of the pain or unsteadiness in the knee. “You can often tell if it’s a bone problem or a ligament problem,” says Dr. Gotlin. This method is satisfactory about 80 percent of the time, he adds.

X-ray: If your doctor is uncertain about the nature of your knee pain, he may recommend an X-ray, which uses low amounts of radiation to record images of your bones and joints. If your knee pain is being caused by a bone problem, such as a fracture or osteoporosis (low bone density), it may show up on the X-ray, Gotlin says.

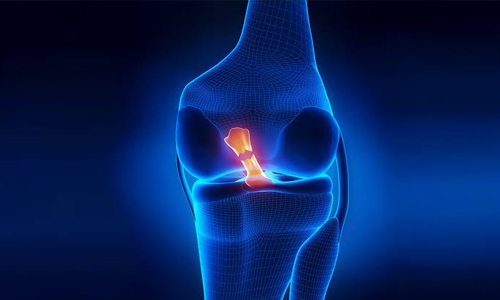

MRI: Short for “magnetic resonance imaging,” this procedure uses magnetic energy to examine the area inside your knee. Unlike X-rays, MRIs can take pictures of the body’s soft tissues, like its muscles and ligaments. For this reason, the procedure is often ordered when a doctor suspects that the soft tissue in the knee is damaged. Contrary to popular thought, MRIs don’t increase a patient’s risk for leukemia or other cancers. “There’s no radiation with an MRI,” Gotlin says.

Ultrasound: This tool used to diagnose knee pain uses sound waves to look inside your knee. Ultrasound is helpful if the doctor wants to inspect the bursa — the fluid-filled cavity inside the knee, Gotlin says. It may also be helpful if there’s excess fluid around the knee — a condition known as effusion. “If there’s any fluid collection or tears of muscles that are very subtle, the ultrasound may be appropriate,” Gotlin says.

Radionuclide bone scan: If your previous diagnostic tests come back normal but your doctor still suspects a problem with the bone, he may recommend a bone scan to check for other problems. “It can pick up cysts, tumors — things that X-rays and MRIs don’t pick up,” Gotlin says. During this procedure, a harmless radioactive substance called technetium is injected into the bloodstream. This substance collects in abnormal or injured areas of the bone, which is then recorded by a scanner. “If there’s a problem, it lights up,” Gotlin says. “If there’s no problem, you get a blank screen.”

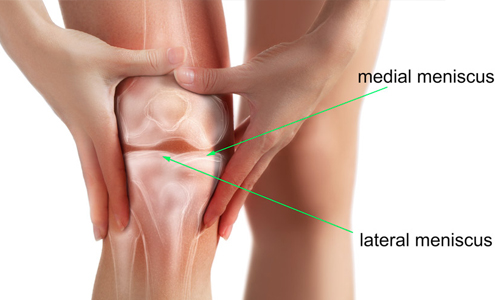

Arthroscopy: During this surgical procedure, a doctor will make small incisions in the knee and insert a pencil-sized instrument called an arthroscope. The arthroscope has a magnifying lens and a light and is attached to a small camera. The images from the camera are then displayed on a television screen, helping the doctor to see the inside of the knee. Once the incision is made, the doctor can diagnose and sometimes treat the source of the knee pain. Tears to the meniscus — a protective piece of cartilage in the knee — can often be corrected during arthroscopy, for example.

With many diagnostic tools at their disposal, doctors can accurately diagnose your knee pain and help you decide on the right treatment option.